On the subject of manual muscle work…

/image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Muscle_spindle_model.jpg

Here is an older article that may seem verbose, but has interesting implications for practitioners who do manual muscle work with their clients. We would invite you to work your way through the entire article, a little at a time, to fully grasp it’s implications.

Plowing through the neurophysiology, here is a synopsis for you:

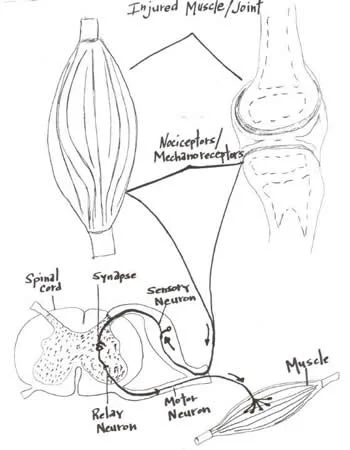

Tactile and muscle afferent (or sensory) information travels into the dorsal (or posterior) part of the spinal cord called the “dorsal horn”. This “dorsal horn” is divided into 4 layers; 2 superficial and 2 deep. The superficial layers get their info from the A delta and C fibers (cold, warm, light touch and pain) and the deeper layers get their info from the A alpha and A beta fibers (ie: joint, skin and muscle mechanoreceptors).

So what you may say

The superficial layers are involved with pain and tissue damage modulation, both at the spinal cord level and from descending inhibition from the brain. The deeper layers are involved with apprising the central nervous system about information relating directly to movement (of the skin, joints and muscles).

Information in this deeper layer is much more specific that that entering the more superficial layers. This happens because of 3 reasons:

there are more one to one connections of neurons (30% as opposed to 10%) with the information distributed to many pathways in the CNS, instead of just a dedicated few in the more superficial layers

the connections in the deeper layers are largely unidirectional and 69% are inhibitory connections (ie they modulate output, rather than input)

the connections in the deeper layers use both GABA and Glycine as neurotransmitters (Glycine is a more specific neurotransmitter).

Ok, this is getting long and complex, tell me something useful...

This supports that much of what we do when we do manual therapy on a patient or client is we stimulate inhibitory neurons or interneurons which can either (directly or indirectly)

inhibit a muscle

excite a muscle because we inhibited the inhibitory neuron or interneuron acting on it (you see, 2 negatives can be positive)

So, much of what we do is inhibit muscle function, even though the muscle may be testing stronger. Are we inhibiting the antagonist and thus strengthening the agonist? Are we removing the inhibition of the agonist by inhibiting the inhibitory action on it? Whichever it may be, keep in mind we are probably modulating inhibition, rather than creating excitation.

Semantics? Maybe…But we constantly talk about being specific for a fix, not just cover up the compensation. Is it easier to keep filling up the tire (facilitating) or patching the hole (inhibiting). It’s your call

Yan Lu Synaptic Wiring in the Deep Dorsal Horn. Focus on Local Circuit Connections Between Hamster Laminae III and IV Dorsal Horn Neurons J Neurophys Volume 99 Issue 3

March 2008 Pages 1051-1052 link: http://jn.physiology.org/content/99/3/1051