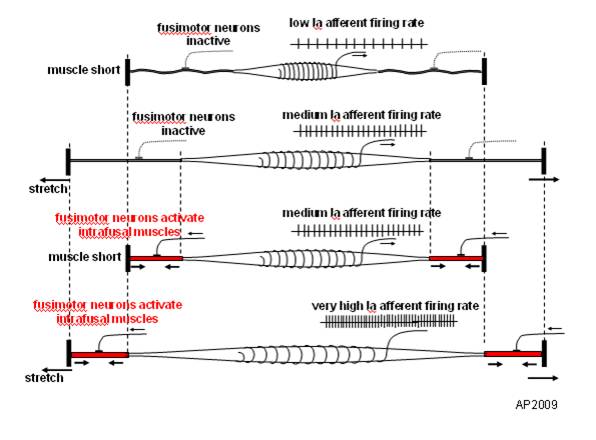

Muscle Spindles and Proprioception

/image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fusimotor_action.jpg

And what have we been saying for the last 6 years?

Connected to the nervous system by large diameter afferent (sensory) fibers, they are classically thought of as appraising the nervous system of vital information like length and rate of change of length of muscle fibers, so we can be coordinated. They act like volume controls for muscle sensitivity. Turn them up and the muscle becomes more sensitive to ANY input, especially stretch (so they become touchy…maybe like you get if you are hungry and tired and someone asks you to do something); turn them down and they become less or unresponsive.

Their excitability is governed by the sum total (excitatory and inhibitory) of all neurons (like interneuron’s) acting on them (their cell bodies reside in the anterior horn of the spinal cord).

Along with with Golgi tendon organs and joint mechanoreceptors, they also act as proprioceptive sentinels, telling us where our body parts are in space. We have been teaching this for years. Here is a paper that exemplifies that, identifying several proteins responsible for neurotransduction including the Piezo2 channel as a candidate for the principal mechanotransduction channel. Many neuromuscular diseases are accompanied by impaired muscle spindle function, causing a decline of motor performance and coordination. This is yet another key finding in the kinesthetic system and its workings.

Remember to include proprioceptive exercises and drills (on flat planar surfaces, like we talked about here) in your muscle rehab programs

Kröger S Proprioception 2.0: novel functions for muscle spindles. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018 Oct;31(5):592-598.

Woo SH, Lukacs V, de Nooij JC, Zaytseva D, Criddle CR, Francisco A, Jessell TM, Wilkinson KA, Patapoutian A. Piezo2 is the principal mechanotransduction channel for proprioception.Nat Neurosci. 2015 Dec; 18(12):1756-62. Epub 2015 Nov 9.

Fusimotor control of proprioceptive feedback during locomotion and balancing: can simple lessons be learned for artificial control of gait?

Hulliger M. Fusimotor control of proprioceptive feedback during locomotion and balancing: can simple lessons be learned for artificial control of gait? Prog Brain Res. 1993; 97:173-80.